As our previous posts described, One Hundred Poets (Hyakunin isshu, hereafter HNIS) is the most famous Waka (Japanese poem) anthology edited by Fujiwara no Teika (1162-1241). Did you know that HNIS was an important educational resource for Japanese women in the late Edo period (1700s-1867)? Our digitized collection has 24 books known to be used for women’s education from the 18th and 19th centuries. These publications not only contain the poems from HNIS but also explain the skills Japanese women were expected to acquire. This post shows some sample items and explores how women in Edo-period Japan were educated using HNIS.

Background: Women’s Education in Edo-period Japan

In pre-modern Japan, education was primarily for the upper-class men who serve the government as samurais.[i] The situation had gradually changed in the late 17th century to mid 18th century, and many “books for women” (josho/nyosho 女書) started to be published to educate and prepare “women for their roles within the patriarchal family system”[ii]. Their learning contents contained home management, self-discipline, courtesy or propriety, and the child rearing. It was strongly influenced by Confucianism from China, which stresses male dominance, integrity and righteousness[iii] [iv].

For instance, one of our digitized items, Onna daigaku takara-bako,女大學寶箱 ([1790]) teaches the moral need for total subordination of women to the needs of the husband and family. It lists 19 expectations for women, such as:

“A woman must ever be on the alert, and keep a strict watch over her conduct. In the morning she must rise early, and at night go late to rest. Instead of sleeping in the middle of the day, she must be intent on the duties of her household, and must not weary of weaving, sewing, and spinning. Of tea and wine she must not drink over-much, nor must she feed her eyes and ears with theatrical performances, ditties, and ballads. To temples (whether Shinto or Buddhist) and other like places, where there is a great concourse of people, she should go but sparingly till she has reached the age of forty.” (Translation by Harper’s Bazaar [v])

(一、女は常に心遣いして、其の身を堅倶謹み護るべし。朝は早く起き、夜は遅く寝ね、昼はいねずして、いえの内の事に心を用い、織り・縫い・績み・緝ぎ、怠るべからず。亦茶・酒など多く呑むべからず。歌舞妓・小歌・浄るりなどの淫れたる事を、見聴くべからず。宮・寺など都ての人のおおくあつまる処へ、四十歳より内は余りに行くべからず。pp.68-71, the pages below)[vi]

In addition to the Confucian values, three other categories were included in female education books:

- Details about everyday life (e.g., clothing, food, marriage, and childbirth),

- Arts (e.g., flower arrangement, tea ceremony, music, calligraphy), and

- Literature.

Literature education focused on reading and understanding waka in 21 imperial anthologies (Nijūichidaishū, chokusen wakashū,二十一代集,勅撰和歌集).[vii] It was different from what male children learned, such as classical Chinese texts. [viii]

How was the One Hundred Poets (Hyakunin Isshu) implemented in women’s education?

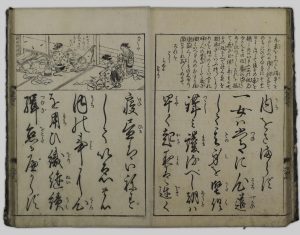

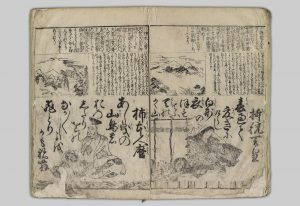

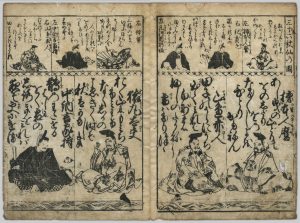

HNIS consists of 100 poems originally contained in 10 imperial anthologies, which is why they were used for female’s literature education. The following pages in [Jokyō banpō zensho azuma kagami] contain each poet’s profile (the upper row), the description of the poem with a picture (the middle row), and the poem with a poet’s portrait (the lower row).

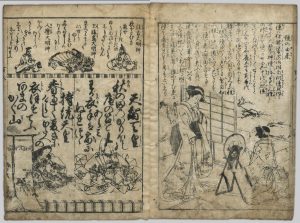

HNIS books contain not only the HNIS poems but also useful tips for women’s lifestyles, such as etiquette, other classical literature, and practical information.[ix] Many books split a page into a couple of sections and depict life hacks in the upper row and the HNIS poems in the lower row. It sometimes uses even one page for picturing general knowledge that is unrelated to HNIS.

For example, in Waka-tsuru hyakunin isshu (稚鶴百人弌首, 1861), the left page explains the origin of mirrors with a picture of women using it. The upper row of the right page depicts the Three Gods of Poetry (Waka sanjin, 和歌三神) namely Sumiyoshi, Tamatsushima, and Kakinomoto no Hitomaro (from left). The lower row shows the first two poems of HNIS by the Emperor Tenji (天智天皇) and the Emperor Jito (持統天皇) (from left).

In addition to HNIS poems, the following pages also introduces other important figures of Japanese literature. The upper row depicts the Thirty-Six Immortals of Poetry (Sanjyu Rokkasen; 三十六歌仙), a group of 36 well-known Japanese poets from 600-1100s. The lower row shows four HNIS poems (From left: Kakinomoto no Hitomaro (柿本人麻呂), Yamabe no Akahito (山部赤人), Sarumaru no Taifu (猿丸大夫), Chunagon no Yakamochi (中納言家持)):

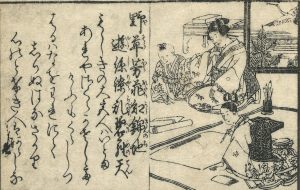

Let’s take a look at other women’s manners depicted in the upper sections. The image below provides a model for calligraphy by depicting a young girl practicing[x]:

The section below explains Ogasawara-ryū orikata (小笠原流折形),the formal way of folding a paper for gift wrapping and decorating.

You can also find sewing patterns of kimono:

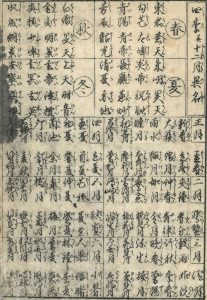

Below is the list of different names used for seasons and months. It includes 8 ways for calling each season (spring, summer, fall, winter) and 13 names for each month (From left upside corner: spring, fall, summer, winter, January, April, February, May, March, June):

As you can see, HNIS books tell us how Japanese women were educated and became literate, and what they learned in the 18th and 19th centuries. Please find more digitized books from our One Hundred Poets Collection.

See also

Past Digitizer’s Blog posts:

- Explore Open Collections: One Hundred Poets | 百人一首 (May 27, 2015)

- Utakagura: a poetry game (April 17, 2018)

Subject in Open Collections

Professor Joshua Mostow, UBC Department of Asian Studies (Owner of the personal collection)

- The One Hundred Poets in the Meiji Period (Digital Meijis)

- Pictures of the Heart: The Hyakunin Isshu in Word and Image (Honolulu: University of Hawai’I Press, 1996)

[i] Bakumatsu-ki no kyoiku. Retrieved from http://www.mext.go.jp/b_menu/hakusho/html/others/detail/1317577.htm

[ii] Ivanova, G. (2016). Re0gendering a classic: “The Pillow Book” for early modern female readers. Japanese Langauge and Literature, 50(1), 105-154. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/24891981

[iii] Kincard, C. (2016, Jun). Gender expectations of Edo period Japan. Retrieved from https://www.japanpowered.com/japan-culture/gender-expectations-of-edo-period-japan

[iv] Sugihara, Y. & Katsurada, E. (2000). Gender-role personality traits in Japanese culture. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 24, 309-318. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2000.tb00213.x

[v] “The greater learning for women.”. (1893, Nov 11). Harper’s Bazaar (1867-1912), 26, 930.

[vi] Onna daigaku (2017, Nov.). Retrieved from https://francois-vidit.com/blog/ja/onnadaigaku

[vii] Ivanova, G. (2016). Re0gendering a classic: “The Pillow Book” for early modern female readers. Japanese Langauge and Literature, 50(1), 105-154. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/24891981

[viii] Hmeljak Sangawa, K. (2017). Confucian learning and literacy in Japan’s schools of the Edo period. Asian Studies, 5(2), 153-166. doi: 10.4312/as.2017.5.2.153-166

[ix] Mostow, J. S. (1996). Pictures of the heart: The Hyakunin Isshu in word and image. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

[x] Mostow, J. S. (1996). Pictures of the heart: The Hyakunin Isshu in word and image. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.