Ready for part 2 of our postings on the cuneiform tablets in the Ancient Artefacts Collection? In the previous post we learned a little about the cuneiform tablets and provenance in general – with a cliff hanger of course.

What IS the provenance of Rare Books & Special Collections cuneiform tablets?

This post we will come closer to finding out. Lisa Cooper, Associate Professor of Near Eastern Art & Archaeology in UBC’s Department of Classical, Near Eastern, and Religious Studies Department, was able to help us start to unravel the mystery.

Arriving at UBC at some time in the early 20th century CE the tablets were accompanied by a typed note intended to provide information about their provenance. However the note was full of, at best, misinformation and at worst? Lies.

The note endowed the tablets with significant cachet – including stating that the tablets had originated in the famed city of Ur (mentioned in the Bible, among other things). It also states that the tablets been excavated through a University dig between 1905 and 1912 by Yale University under the direction of Professor A.T. Clay. Sounds pretty important doesn’t it? Too bad not one part of it is true.

We know today the first excavation of Ur wasn’t until 1922 – by the British Museum and the University of Pennsylvania. The professor in question, A.T. Clay, didn’t even visit Mesopotamia until 1920, about 10 years after the dates indicated in the notes.

So where did these tablets come from? How were they found? Who brought them to UBC?

We still don’t know all the answers to these questions, but we are starting to learn more. Unprovenaced items like the RBSC tablets can end up being the subject of much discussion. The debate centers around the morality and legality of the acquisition of these items by western institutions. For more information on that debate, check out Professor Lisa Cooper’s UBC news piece on antiquities from the Middle East.

The little we can conjecture about the RBSC tablets is that they were likely purchased in an antiquities market in the early 20th century.

Someone may have translated the tablets, seen the Third dynasty of Ur marking the era, and mistakenly believed the tablets were from Ur. The mistranslation could have been because the tablets were originally translated 50-60 years ago – before we have the knowledge of the past we do now.

Put that misinformation together with someone looking to make a profit, or even just guessing at a possible provenace, and volia! You have items originating out of thin air.

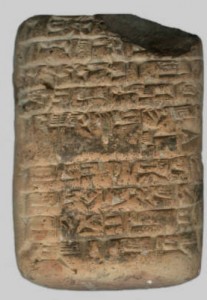

Due to contextual information in the tablet writing, we now believe that three tablets originate from the Umma region and two come from Puzrish-Dagan region. As well, recent scholarship dates the reigns of Shulgi and Amar-Sin – the two kings mentioned in the tablets – to almost 300 years earlier than originally thought.

Tomorrow, who knows? With the provenance of many ancient items, including ones such as these, there is always more to uncover.